Red Cross Lifeguard Surveillance Guidelines

This critical information is republished from The American Red Cross

Scanning Techniques

Last Full Review: American Red Cross Scientific Advisory Council, 2020

Last Update: 2023

Lifeguards need to quickly identify swimmers in distress and drowning persons in order to rapidly come to their aid to prevent drowning. Lifeguards spend a majority of their on-duty time scanning bathers and swimmers in the water. Scanning is a visual surveillance technique that lifeguards use to protect patrons. While on surveillance duty, lifeguards are required to deliberately and actively scan their zone of responsibility. To be able to accomplish this task, lifeguards need specific and extensive training in visual surveillance and scanning skills.

Lifeguards also need to identify the behavioral patterns associated with drowning persons and swimmers in distress. A typical drowning is not what has been popularized in the press or in movies that show a person calling for help and waving their arms about. The person is usually unable to call out because their mouth is underwater and instead, they use arm movements that press down on the water’s surface.

Red Cross Guidelines and Best Practices

- Surveillance should begin in the lifeguard’s assigned zone by scanning from point-to point quickly, thoroughly and repeatedly.

- Lifeguards should move their head and eyes and look directly at each area of the assigned zone and each person in the assigned zone.

- Lifeguards should adjust body position or stand up as needed to gain better visibility.

- With each scan of the assigned zone, the lifeguard should search:

- The entire volume of water, including the bottom, the middle and the surface.

- The areas under, around and directly in front of the lifeguard station.

- The areas around play features or other structures.

- Each scan of the entire zone should be completed within 30 seconds.

- Lifeguards should continue scanning the assigned zone throughout the entire time on the stand.

- The use of virtual reality may be considered as an alternative instructional method to promote acquisition of effective surveillance and scanning skills.

Evidence Summary

A 2023 scientific review (American Red Cross Scientific Advisory Council 2023) of a 2020 American Red Cross Scientific Advisory Council systematic review identified eight publications that supported the evidence in the previous scientific review.

The 2020 systematic review reported that, generally, the work on the topic of visual surveillance or scanning falls within the broad theoretical area of human information processing. Signal detection theory is an important related theoretical construct to information processing theory that is applied to lifeguarding. The signal detection theory acknowledges that vast amounts of stimuli, including visual stimuli, bombard humans constantly (Langendorfer, Francesco and Beale-Tawfeeq 2022, 8). The goal of signal detection theory is to measure the ability of humans to differentiate between stimuli (“signals”) that are information-bearing from random background patterns (“noise”). This process is at the heart of a lifeguard’s role while on duty, which is detecting a “signal” (i.e., a person in distress or drowning) from all the other visual, auditory and tactile stimuli in the environment.

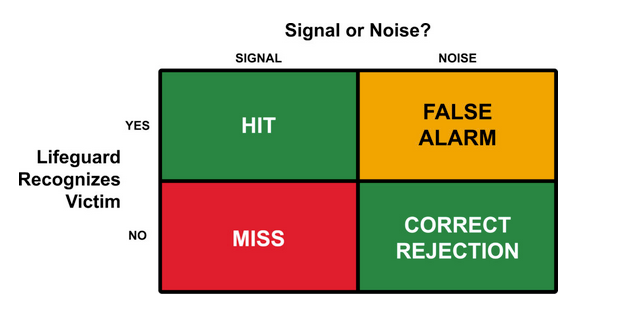

In signal detection theory, a lifeguard on duty can have four possible outcomes:

- A hit: There is a person in distress or drowning and the lifeguard detects and recognizes the situation and responds.

- A miss: There is a person in distress or drowning and the lifeguard does not detect them.

- A false alarm: There is no person in distress or drowning, but the lifeguard believes they detect a person in distress.

- A correct rejection: There is no person in distress and the lifeguard correctly does not respond.

Hits (1) and correct rejections (4) are good outcomes; misses (2) and false alarms (3) are bad outcomes (although a miss is much more serious to a lifeguard than a false alarm) (See Infographic: Hit, Miss, False Alarm, Rejection).

Two studies using convenience samples of United States lifeguards identified that research subjects were often were not better at recognizing drowning events than non-lifeguards (Lanagan-Leitzel 2012, 5; Lanagan-Leitzel and Moore 2010, 4). Studies from the United Kingdom found that British lifeguards were in fact superior to non-lifeguards (Harrell and Boisvert 2003, 129; Laxton and Crundall 2018, 14; Page et al. 2011, 216) in scanning and identifying drowning events, although they noted that even experienced lifeguards frequently missed passive drowning.

One strong trend revealed in a number of studies was the importance of experience and expertise in scanning (Biggs et al. 2013, 330; Bowden and Loft 2016, 2011; Nordfang and Wolfe 2018, 285; Page et al. 2011, 216; Van der Gijp et al. 2017, 765). Among persons with expertise in various types of visual scanning or surveillance (e.g., radiologists, air traffic controllers, athletic referees), the experience gained either from specific training, education or experiential/trial-and-error time-on-task always provided faster and more reliable, consistent results than non-experts or those with limited experience. These studies further reinforced the theme that aquatic managers must provide more extensive training and practice in identifying drowning persons as part of an ongoing in-service training program.

Several lifeguard training programs in the United States have advocated for specific types of temporal or spatial search patterns (e.g., A, B, geometric patterns). The evidence-based literature did not support such strategies or artificial devices because they in fact distracted observers from the primary target (i.e., distressed or drowning persons) as a result of requiring internal perceptual processes (Annerer-Walcher et al. 2020, 3432). Indeed, lifeguards must be taught to store in their long-term memory those behavior patterns in the water that indicate a person is in distress or drowning (e.g., the instinctive drowning response, a vertical body position, lateral downward pressing of arms, failure to swim to safety) (See Infographic: Human Information Processing).

The most recent literature review identified studies (Lim et al. 2023, 103954) suggesting that visual surveillance and scanning can be more effective if the instructional method of delivery explores the use of virtual reality (VR) to promote the acquisition of effective surveillance and scanning skills. The research provides justification and support for the construct validity of VR simulations as a potential training tool, allowing for improvements in the fidelity of training solutions to improve pool lifeguard competency in drowning detection. One study (Wright et al. 2020, 339-1) reported that the use of VR allowed participants to practice head rotation skills and allowed guards to practice skills in dangerous conditions, such as fog and large crowds, with the receipt of immediate feedback to improve and refine these skills.

Insights and Implications

The majority of a lifeguard’s time is spent scanning bathers and swimmers in the water and not responding to a drowning. Consequently, a lifeguard’s vigilance can suffer because the signal detection process requires attentional focus and is perceptually fatiguing. The challenge for new lifeguard candidates in training is to be able to recognize a correct signal of a distressed or drowning person. Aquatic managers should be aware of the need to maintain optimal attention and vigilance by lifeguards (e.g., give much more frequent breaks especially under heavy bather loads; use shifts in physical posture; avoid distractions).

Lifeguards need to be knowledgeable and skilled in effective visual scanning of persons in the water. The capacity to visually scan effectively depends on both knowledge and training plus sufficient attention, vigilance and lack of internal and external distractions. Aquatic facilities and aquatic managers should make certain that lifeguards are alert and attentive so they can recognize a distressed or drowning person.

Vigilance

Last Full Review: American Red Cross Scienti8c Advisory Council, 2020

Last Update: 2023

To be effective, a lifeguard must be vigilant (i.e., continuously mentally alert and attentive) while conducting surveillance. Being vigilant while on the lifeguard stand is a key component of effective surveillance. Maintaining the continuous concentration needed to remain vigilant while scanning is difficult and fatiguing. While conducting surveillance, a lifeguard’s ability to stay focused and pay attention declines, which is called vigilance decrement. To counteract vigilance decrement, aquatic facilities should develop and implement strategies.

Red Cross Guidelines and Best Practices

- Lifeguards should receive training to avoid inattention and distractions (e.g., talking to patrons, using cell phone, daydreaming) while on duty.

- Lifeguards should receive training in simple ways to improve attention (e.g., getting enough rest, performing simple physical change of posture movements).

Evidence Summary

Vigilance is defined as “one’s ability to focus attention and detect signals for an extended period of time under conditions where signals are intermittent, unpredictable and infrequent” (Lanagan‐Leitzelm, Skow and Moore 2015, 425). Research has shown that vigilance decreases over time when a lifeguard is assigned to a specific task, such as surveillance duty (Esterman et al. 2014, 2287).

An American Red Cross Scientific Advisory Council scientific review (American Red Cross Scientific Advisory Council 2020) included several studies that identified factors that detracted from successful performance of visual scanning and surveillance. One study (Sebastiani et al. 2020, 48) reported that vigilance degradation detracted from performance of scanning tasks—suggesting an increase in critical “misses” of distressed or drowning persons by lifeguards. These findings suggest a closer review of current lifeguard practices (e.g., length of on-duty time which causes a severe decrement in attention and visual performance searches).

Two studies identified visual assessment instruments that might be employed effectively in the training and monitoring of lifeguards. Deering et al. (Deering et al. 2018, A391) published a 3-minute revision (from the original 10-minute instrument) of the Psychomotor Vigilance Test that might be a useful instrument to employ while training lifeguard candidates and perhaps as part of field audits. Sanchez-Lopez et al. (Sanchez-Lopez et al. 2019, 116) described the use of eye-gaze contingent attentional training (ECAT) that also showed promise in maintaining performance through improved attention.

Insights and Implications

The capacity of a lifeguard to perform effective visual scanning depends on both knowledge and training plus sufficient attention, vigilance and lack of internal and external distractions (Langendorfer, Francesco and Beale-Tawfeeq 2022, 8). This information has implications for aquatic facilities and aquatic managers to make certain that lifeguards are alert and attentive so they can recognize distressed or drowning people.

The Red Cross offers suggestions for techniques to help improve a lifeguard’s ability to stay vigilant (American Red Cross. Lifeguarding: Participant’s Manual. Chapter 9: CPR & AED. 2024):

- Maintain an active body posture.

- Change position often.

- Get enough rest before reporting for a lifeguard shift.

- Stay hydrated.

- Cool off during breaks.

- Engage in some form of light exercise during breaks to keep energy up.

Inattentional Blindness

Last Full Review: American Red Cross Scienti8c Advisory Council, 2020

Last Update: 2023

Inattentional blindness occurs when a person completely misses something in their line of sight because they are focused on something else, and a new or different stimulus is unexpected. Effective surveillance requires attention, focus and concentration while on the lifeguard stand. Several distractions, such as by one’s own thoughts, may be present during this time that may lead a lifeguard to inadequately fulfill their current responsibilities.

Red Cross Guidelines and Best Practices

- Lifeguards should receive training to avoid inattention and distractions (e.g., talking to patrons, using cell phone, daydreaming) while on duty.

- Lifeguards should receive training in simple ways to improve attention (e.g., getting enough rest, performing simple physical change of posture movements).

Evidence Summary

A number of studies have reinforced the difficulties associated with visual scanning and surveillance and the factors that detracted from successful lifeguard performance. For example, misplaced errors associated with selective attention (Conci and von Mühlenen 2011, 203), inattentional blindness (Eitam, Shoval and Yeshurun 2015, 125), expectation violations (Foerster and Schneider 2015, 45) and vigilance degradations.

A 2020 American Red Cross Scientific Advisory Council scientific review included several studies that identified factors that detracted from successful performance of visual scanning and surveillance. One study (Sebastiani et al. 2020, 48) reported that vigilance degradation detracted from performance on scanning tasks—suggesting an increase in critical “misses” of distressed or drowning persons by lifeguards. These findings suggest a closer review of current lifeguard practices (e.g., length of on-duty time, which can cause a severe decrement in attention and visual performance searches).

Two studies identified visual assessment instruments that might be employed effectively in the training and monitoring of lifeguards. Deering et al. (Deering et al. 2018, A391) published a 3-minute revision (from the original 10-minute instrument) of the Psychomotor Vigilance Test that might be a useful instrument to employ in training lifeguard candidates and perhaps as part of field audits. Sanchez-Lopez et al. (Sanchez-Lopez et al. 2019, 142) described the use of eye-gaze contingent attentional training (ECAT) that also showed promise in maintaining performance through improved attention.

Insights and Implications

Lifeguards are at risk for inattentional blindness when they focus on one aspect of scanning (e.g., identifying distressed swimmers and active drownings at the surface of the water) at the expense of another (e.g., identifying submerged drownings). Because submerged drownings are rare, a lifeguard may not expect to see one and as a result, may not recognize a submerged drowning even when the person is right in front of them.

Inattentional blindness can also occur when a lifeguard is distracted (e.g., talking to patrons or other staff). Mental activities such as daydreaming and following a specific pattern when scanning or mentally rehearsing a rescue can also cause inattentional blindness—leading to missed signals and a failure to identify patrons in need of help. The lifeguard is looking, but not seeing, in much the same way a driver who is distracted by a conversation or their own thoughts may be looking at a traffic light, but not see it turn green.

The Red Cross offers suggestions for strategies to avoid inattentional blindness while conducting surveillance (American Red Cross Scientific Advisory Council 2023):

- Maintain an active body posture.

- Change position often.

- Get enough rest before reporting for a lifeguard shift.

- Stay hydrated.

- Cool off during breaks.

- Engage in some form of light exercise during breaks to keep energy up.

Visual and Behavioral Cues

Last Full Review: American Red Cross Scienti8c Advisory Council, 2020

Last Update: 2023

Drowning is a leading cause of unintentional injuries in the United States. There are more than 4000 unintentional fatal drownings each year in the U.S. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2023). Effective surveillance enables a lifeguard to identify situations and behaviors that can lead to life-threatening emergencies, such as drowning. Visual cues are part of the scanning process where a lifeguard is able to recognize when a person is in trouble. Additionally, recognizing the behaviors of a distressed swimmer, active drowning person or passive drowning person are part of effective surveillance.

Red Cross Guidelines and Best Practices

- Dangerous situations and behaviors, if not corrected, should be corrected before becoming life-threatening.

- Novice lifeguards should receive sufficient structured online video training and practice to acquire effective visual scanning to readily identify typical behavioral patterns of drowning persons.

Evidence Summary

A 2020 American Red Cross Scientific Advisory Council scientific review focused on surveillance and scanning skills and the methods of teaching these skills to lifeguards so that they competently perform their surveillance duties.

The systematic review of the literature noted that the identification of a distressed or drowning person’s behavioral patterns is not readily understood (Carballo-Fazaneset et al. 2020, 6930). However, lifeguards need to accurately and reliably identify a distressed or drowning person by recognizing distinctive behavioral patterns (e.g., instinctive drowning response, vertical posture in water, lateral downward pressing of arms, lack of capacity to swim to safety) (American Red Cross Scientific Advisory Council 2020).

A drowning incident that occurs in a lifeguard-supervised area is often due to the failure of a lifeguard to recognize signs of a struggle, intrusion of non-lifeguard duties and distraction from surveillance duties (Pia 1984, 52). The “RID” factor is an acronym that suggests that when a drowning incident occurs in a lifeguard-supervised area, one or more of the three letters were a factor. The letter R stands for “Recognition failure,” in that the lifeguard fails to recognize that a person is in distress or drowning. The letter I stands for “Intrusion of the primary responsibility of surveillance” as a lifeguard was replaced with secondary duties. Examples of secondary duties are maintenance tasks, such as sweeping the deck, picking up trash or other non-surveillance-related activities. The letter D stands for “Distraction of a lifeguard” while on surveillance duty. Examples of distraction include socializing with a patron or another employee of the facility, or using electronic devices that interfere with primary surveillance duties (Pia 1984, 52).

Visual scanning to detect distressed or drowning persons requires a degree of experience that can be attained by trial-and-error over years or through hours of structured training. One recommendation made by the 2020 American Red Cross scientific review is that the American Red Cross must provide structured training in visual scanning and detection of behavioral drowning patterns to lifeguard candidates to better prepare them for identifying distressed and drowning persons.

Insights and Implications

Conducting surveillance is how a lifeguard fulfills their primary responsibility, which is to protect lives. With effective surveillance, a lifeguard can recognize behaviors or situations that might lead to life-threatening emergencies, such as drowning, and then quickly intervene to stop the behavior or change the situation. However, effective surveillance relies on knowing which situations and behaviors to look for.

Non-swimmers or inexperienced swimmers may encounter trouble in the water as a result of excitement or lack of knowledge about dangers. For example, a non-swimmer or inexperienced swimmer may be a person who is (American Red Cross Scientific Advisory Council 2023):

- Bobbing in or near water over their head.

- Crawling hand-over-hand along a pool wall, toward deeper water.

- Out of arms’ reach of a supervising adult.

- Clinging to something or struggling to grab something to stay afloat.

- Wearing a lifejacket improperly.

- Using water wings or pool toys that creates a false sense of security. This could lead them to deeper water where they fall off of a pool toy setting up the potential for a drowning situation.

The Red Cross recommends that dangerous situations and behaviors should be identified and corrected before they become life-threatening. The Red Cross also recommends that novice lifeguards receive sufficient structured online video training and practice to acquire effective visual scanning and thus readily identify typical behavioral patterns of drowning persons.

Scheduled Breaks to Reduce Vigilance Decrement

Staying alert and focused while a lifeguard performs surveillance duties requires concentration and attentiveness. Maintaining the continuous concentration needed to remain vigilant while scanning is difficult and fatiguing. During a lifeguard’s time on the stand, the ability to stay focused and pay attention declines. This is defined as vigilance decrement. How long should a lifeguard be assigned to continually watch the water before interruption of this duty?

Red Cross Guidelines and Best Practices

- To reduce vigilance decrement, lifeguards should have scheduled breaks from surveillance duty (e.g., a 10- to 15-minute break every hour).

Evidence Summary

Research has shown that vigilance decreases over time when a lifeguard is assigned to a specific task, such as surveillance duty (Esterman et al. 2014, 2287). An experimental study conducted in 2014 (Ross, Russell and Helton 2014, 1729) provided rest breaks after performing a difficult task. The study reported that providing a 1-minute break after 20 minutes slightly improved vigilance. However, after providing an additional 10-minute break, vigilance did not improve. Rest breaks were associated with reduced self-reported effort and temporal demand. A second study (Arrabito et al. 2015, 1403) investigated the effects of a rest break intervention during a 40-minute auditory and visual vigilance task. A short rest break was reported to restore detection accuracy in both auditory and visual tasks during a 40-minute watch following deterioration in performance. Therefore, having a limit on the amount of time spent on surveillance with frequent breaks is supported through research studies.

Insights and Implications

To counter vigilance decrement, research studies support the recommendation that lifeguards should have scheduled breaks from surveillance duty. At a minimum, a scheduled break of 10- to 15-minutes from surveillance duty is recommended to improve vigilance.